What Norway Taught Me About Women - by Camille Saunders

For a long time now, I have wanted to come to Norway to experience why it has consistently topped international charts relating to human rights and gender equality (#1 overall when taking into consideration the 2023 Freedom in the World Index, Index of Economic Freedom, Press Freedom Index and Democracy Index). In 2022, Norway ranked #6 in the World Happiness Index Report, behind Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Switzerland and the Netherlands. I think I assumed it would be an unadulterated heaven of pure joy and acceptance, and now that I have enjoyed the privilege of interrailing there with my brother this past fortnight, despite this being a difficult bar to achieve, it comes extraordinarily close.

Needless to say, Norway has its own struggles too, for example a higher suicide rate especially during the long, dark winters. Furthermore, in a bid to curb alcoholism by taxing drinks out of anyone’s price range and not selling them past 6pm except in specific bars, falling prey to drugs is a much smaller leap from the beaten path; a fact we discovered on our first day in Oslo where the main street between the station and our hostel was lined on both sides with an ever-growing crowd of people openly doing and dealing and never a police intervention.

However, not only is the scenery as spectacular as anyone could dream of, but the people were also visibly happier, friendlier and eager to help. Without even needing to ask, they offered us directions whenever we looked lost, always delivered in better English than our own. Every time we got on public transport, the person opposite made eye-contact, smiled and nodded. Buses even had adverts telling people to smile more as it would make the other passengers more comfortable. Nobody locked their bikes because nobody stole them. The ticket inspectors on the train had banter with every passenger and even hung out with their favourite groups in between stations sharing jokes and stories as though they were old friends. There were no barriers at the train station to get on without a ticket, and buses and trams opened the middle door for people to get on without even passing the driver, let alone having ticket inspectors to check if you had tapped in; people simply respected the system enough to pay the ticket fare anyway, knowing that it was contributing to their driver’s salary. On top of being swathed in natural light and incandescent views of the fjords, the city trams played lo-fi music to announce each new stop, and the ceiling was decorated with calming watercolour paintings of root vegetables. Ever looked up in a London tube? The art is more in the style of slurs carved in with car keys, old chewing gum and graffiti of genitalia.

Perhaps all this happiness and relaxation is why the rate of sexism and misogyny is so much lower: simply put, when people are happy, they have nothing to prove.

To that end, I decided the best way to present my findings was completely neutrally, with no agenda or pretence of understanding Norwegian culture as an outsider. I will simply keep track of what I have learnt, not about the general place of women, which is such a complex question that I would never succeed on such little research as a two-week trip, but rather individual women that I hope you will find as interesting as I did. Feel free to scroll down to a title that catches your interest; and if you ever get a job offer in Norway, I would suggest you jump at the opportunity.

Skiing, herding reindeer and running the Sami parliament

Norwegian Museum of Cultural History, Oslo

Hand on heart, I came to Norway knowing cleanly nothing about Sami history, identity or culture, and therefore I am grateful to this museum for having such a detailed exhibit dedicated to them. In the first window, we are already presented with a gender parity from five centuries ago. According to the Swedish scholar Olaus Magnus’s 1555 history of Nordic peoples, skis were used on hunting expeditions by the Sami, equally by the women as by the men. In fact, while like in many cultures, spinning and weaving fell to the women, the needles to make traditional Sami patterns were light-weighted so that women could take them with them when herding reindeer, in which, much like hunting, they participated equally to the men.

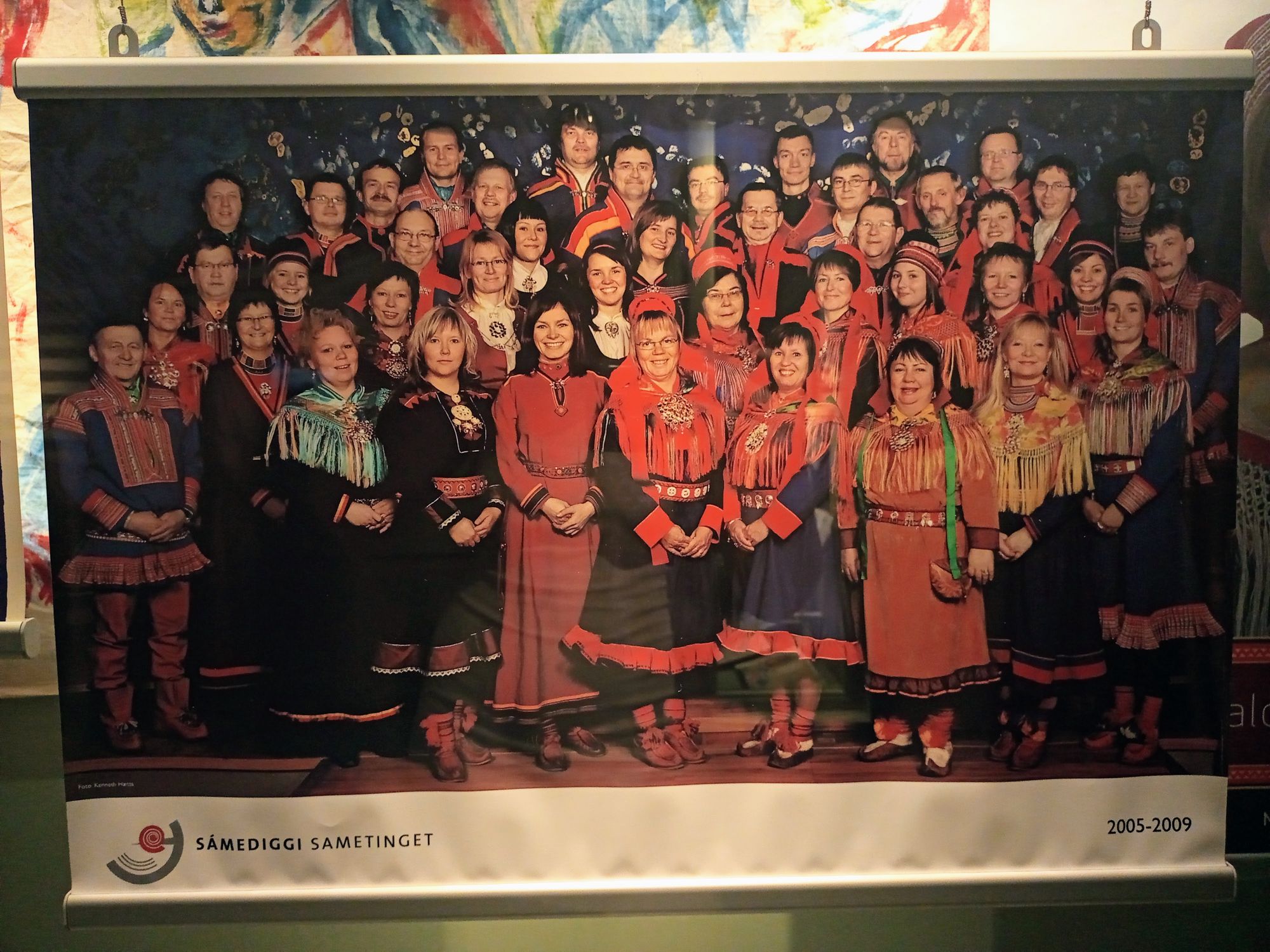

When we wind the clock forward to more recent history, these examples of equality are reflected in other ways. For example, from the 2005-2009 photo of the Sami Parliament, established in 1989, there are 22 men and 22 women, thus an exact 50:50 male-female ratio. The Norwegian Parliament is currently split 55:45 (Statista, 2021), and the UK government is 69:31 (gov.uk, 2022).

Odin in drag, the afterlife, and a chocolate fertility goddess

‘Viking Planet’ Museum, Oslo

One representation of women in this museum was the importance of the goddess Freja (/Freya/Freia) of fertility and marriage, as shown by the amber cat artefact kept as a symbol of her and thought to have been lost in a marketplace in the town of Birka. It is thought to have been made as an amulet to ensure a large, healthy family, as Freja’s chariot was believed to have been drawn by two cats, Bygul and Trjegul. Even now, one of the largest chocolate companies in Norway, which you can buy from any shop, anywhere, is called “Freia” and we even passed entire freight carriages of it on the railway.

The museum also draws our attention to a small figurine of Odin, the king of the gods, wearing a woman’s dress and a pearl necklace, with a caption explaining that “Odin was a god who transcended sex and normal conduct, so it is possible he is sitting on this throne in drag.” Another explanation given is that he is channelling the power of the Volva, the title given to great female shamans.

The Volvas were hugely respected figures of Viking society, as they were believed to see into the future and communicate with the beyond. These women were invited into people’s homes, fed a hearty meal and often paid huge amounts of silver; Germanic Volvas in accounts from the Roman era even held authoritative positions not only above their own tribes, but above the Romans. It was not until the Christianisation of Scandinavia and the Malleus Maleficarum laws that they were persecuted; rather, they were always previously revered and respected.

Finally, the museum explains to us that several silver pendants exist showing female warriors, suggesting that women may have fought alongside men. Others depict Valkyries, female figures which guide the souls of the slain to the afterlife. Even here, we have been misled by modern depictions of the Vikings as going to Odin’s land of Valhalla after death, when in fact Freja chose her favourite soldiers first, and these chosen souls went to her realm of Folkvang.

The female pirate who took on the Hanseatic League (and won)

Stavanger Maritime Museum, Stavanger

The first example this museum showcased in their ‘Seafarers in the 20th Century’ exhibit was Frida Dahlberg, who worked as a radio operator from 1958-60 on the Høegh Ariane ship, which sailed between France and West Africa, exchanging flour, wine and cars for peanuts and timber. For much of Dahlberg’s career she was the only woman in a crew of more than 30 men, going to sea for months at a time, however female presence on ships increased throughout the 1950s, from 11% in 1952 to 24% in 1967.

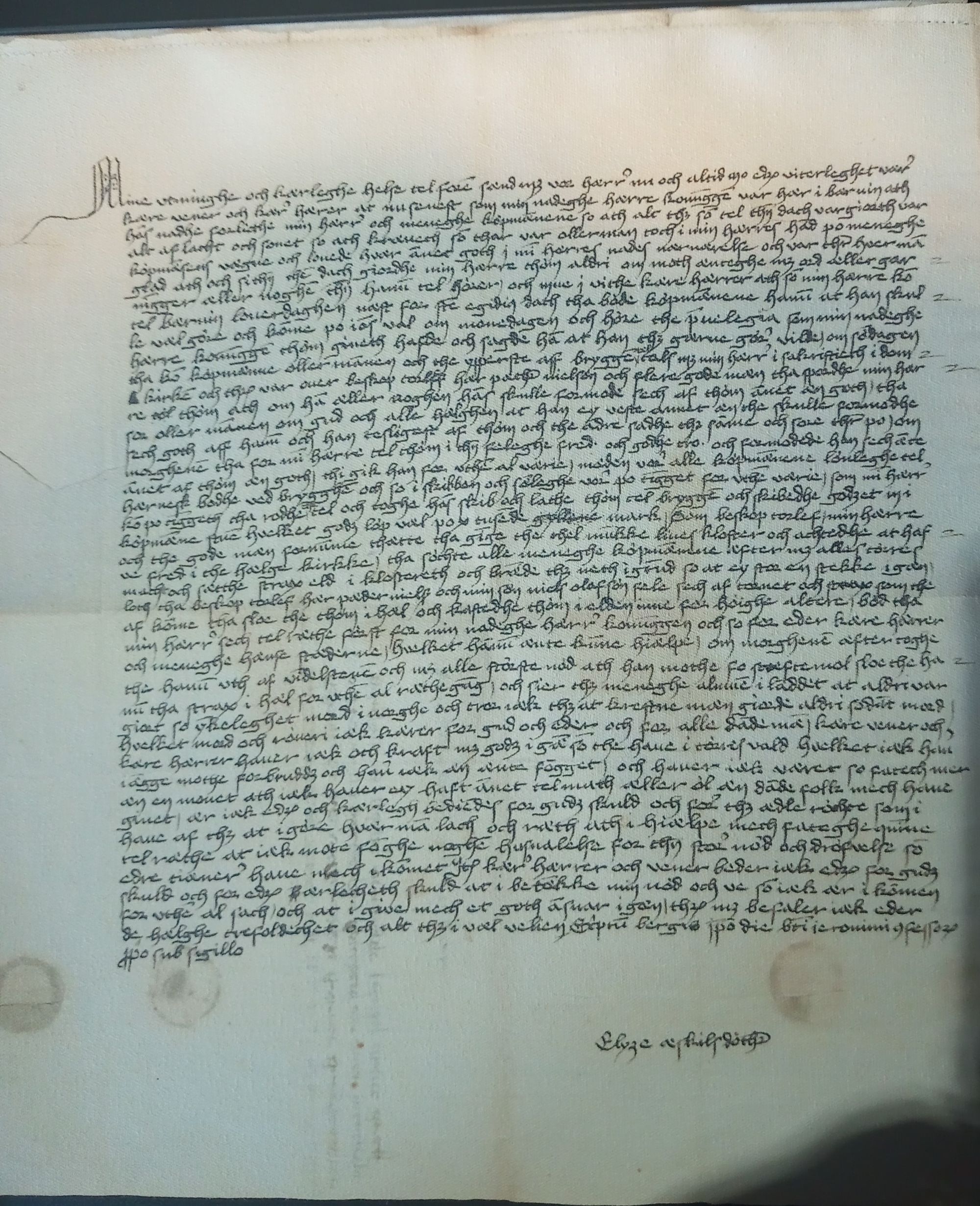

Another woman hailed in the museum is Elise Eskildsdatter, a pirate from the mid-1400s, married to a knight from Stavanger, Olav Nilsson. She was responsible for the capture of several Hanseatic merchant ships, as her and her husband believed the Hanseatic League held too much power across Northern Europe. However, in 1455, the League allied with the King and sought revenge. They killed Olav and his son, plundered their estate and then seized the land. Luckily, Elise wrote letters of complaints to the King, the Hanseatic Council in Lübeck, and the Pope, demanding compensation for her family and her estate. Eventually, after 40 years of feuding, in 1490 the Hanseatic merchants were forced to pay a fine. Elise’s letter is preserved in the Hansa City Lübeck archives, and it is how we know of her existence, her literacy, and her incredible determination.

Finally, in the ‘Women and Trade’ exhibit, the museum tells us that women were also involved in trade, not just men, provided they were widows, or had permission from their male guardian (husband, brother or father). Many married women also ran the stores and shops in the trading houses, but some also engaged in international trading.

Modern art

Bergen Kunsthall, Bergen

The Bergen Kunsthall Museum was showing an exhibit by modern artist Camille Norment, building on a principle called “cultural psychoacoustics”. The museum described this as meaning “an investigation of socio-cultural phenomena through sound and music”, and that Norment particularly emphasises “sonic and social dissonance, an agency of listening, and the empowerment and transformative possibilities of sound.”

For example, the first exhibit included a framed phrase on each wall relaying the first ever human ‘conversation’ of when anthropologists believe the first grunts were used as communication, thus producing a loop between the four walls, reminding us that whenever we communicate, we are inherently tied to these cavewomen from 50,000-100,000 years ago.

The second exhibit comprised three rooms, each producing a different sound and a different effect on the others. A marble rattling through a metal pipe made the floor vibrate slightly, making the wooden seats vibrate slightly, making the giant brass teardrop hanging from the ceiling in the next room vibrate and produce a loud, low-pitched moaning sound. The sound coming from a pair of headphones attached to the wall then made the brass bowl balancing on them vibrate, thus making the metal balls inside roll around as if by themselves, reminding us that even when things seem to happen independently, there is a cause and effect; this could either make us think back to our origins, such as a divine creator, or look to the future, such as the Butterfly Effect, that even the smallest movements and decisions can have much greater impacts elsewhere.

Music and gender

Ringve Musik Museum, Trondheim

The Ringve Music Museum was founded by Victoria Bachke, and the museum makes it clear that “without her zeal and determination, the country estate would never have become the cultural centre it is today.” After moving from Russia to Switzerland to cure her tuberculosis, the First World War prevented her from returning home, and having lost all contact with her family due to the war, she moved to Norway with her sister where her uncle had escaped to. Having survived this war, she then also defended her collection of musical instruments throughout the Nazi occupation during the Second World War, as they wanted the space to build an airstrip. When her beloved husband passed away in 1946, she turned her home and her instrument collection into a museum in his honour, travelling the world to obtain more – there are now more than 350 different types of instruments in their gallery. The concept of determination permeates the museum, both by having protected the collection from two world wars, but also as an individual: the museum says, “if there was something that she wanted, she didn’t give up, but used all her charm, endurance and powers of persuasion” and was a “ruthless haggler,” without which the museum never would have existed.

Part of their exhibit is called ‘Music and Gender’; this was something I noticed in all the museums we went into, as there was clearly a concerted effort to represent the sexes equally. They explained about the mimicry of instruments with male and female bodies, noting that instruments such as the cello had feminine curves, whereas shapes such as a trumpet’s were more associated with masculinity. They also pointed out the social aspect of playing different instruments:

“Sitting quietly at the piano was the ideal for middle class daughters during the 1800s. Wind instruments that required musicians to use their lips and facial muscles to play were deemed indecent for women to play. In German nunneries, the trumpet was replaces with a string instrument having a trumpet like sound: the trumpet marine (tromba marina).”

by Camille Saunders

Credits: all quoted information comes from the museum as named in the titles, and all photos are my own